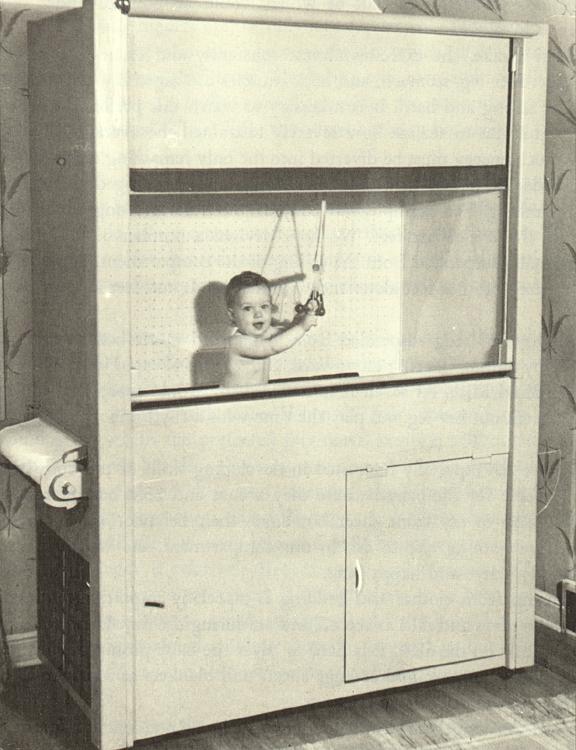

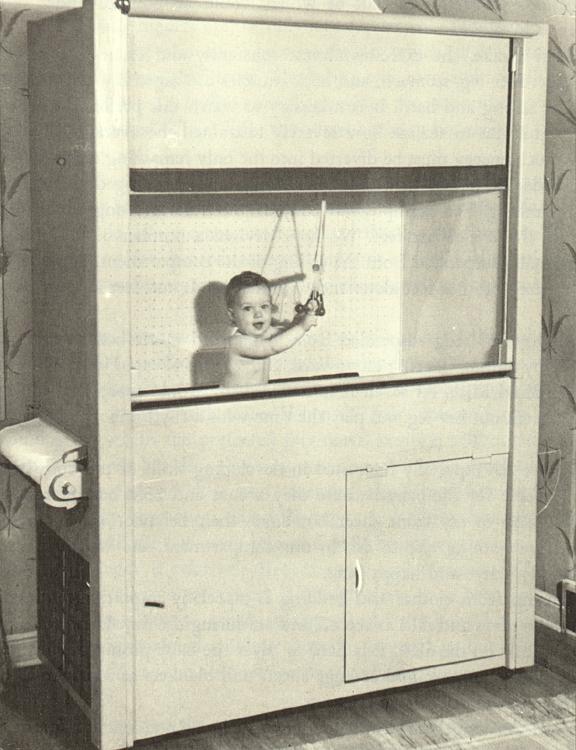

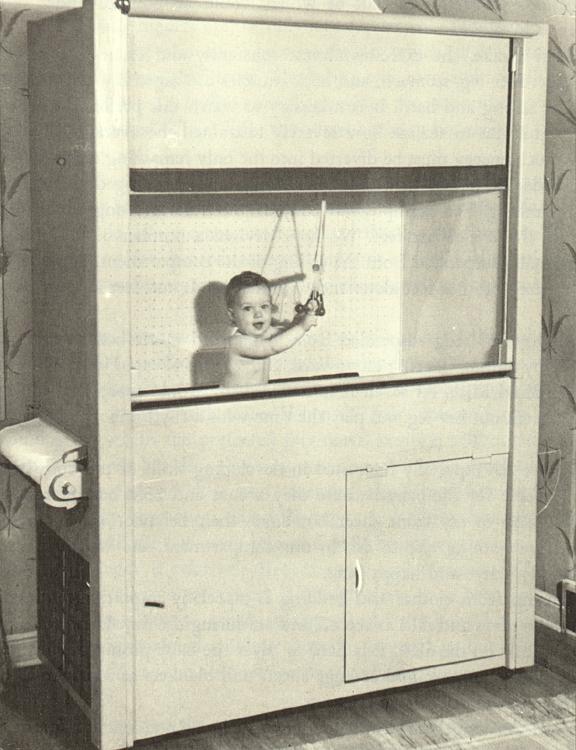

BABY IN A BOX

B.F. Skinner

Ladies Home Journal,

October 1945

In that brave new world

which science is preparing for the housewife of the future, the young mother has

apparently been forgotten. Almost nothing has been done to ease her lot by

simplifying and improving the care of babies.

When we decided to have another child, my

wife and I felt that it was time to apply a little labor-saving invention and

design to the problems of the nursery. We began by going over the

disheartening schedule of the young mother, step by step. We asked only

one question: Is this practice important for the physical and

psychological health of the baby? When it was not, we marked it for

elimination. Then the “gadgeteering” began.

The result was an inexpensive apparatus in

which our baby daughter has now been living for eleven months. Her

remarkable good health and happiness and my wife’s welcome leisure have

exceeded our most optimistic predictions, and we are convinced that a new deal

for both mother and baby is at hand.

We tackled first the problem of warmth.

The usual solution is to wrap the baby in half-a-dozen layers of cloth-shirt,

nightdress, sheet, and blankets. This is never completely successful.

The baby is likely to be found steaming in its own fluids or lying cold and

uncovered. Schemes to prevent uncovering may be dangerous, and in fact

they have sometimes even proved fatal. Clothing and bedding also interfere

with normal exercise and growth and keep the baby from taking comfortable

postures or changing posture during sleep. They also encourage rashes and

sores. Nothing can be said for the system on the score of convenience,

because frequent changes and launderings are necessary.

Why not, we thought, dispense with

clothing altogether-except for the diaper, which serves another purpose-and warm

the space in which the baby lives? This should be a simple technical

problem in the modern home. Our solution is a closed compartment about as

spacious as a standard crib (Figure 1). The walls are well insulated, and

one side, which can be raised like a window, is a large pane of safety glass.

The heating is electrical, and special precautions have been taken to insure

accurate control.

After a little experimentation we found

that our baby, when first home from the hospital, was completely comfortable and

relaxed without benefit of clothing at about 86°F.

As she grew older, it was possible to lower the temperature by easy stages.

Now, at eleven months, we are operating at about 78°,

with a relative humidity of 50 per cent.

Raising or lowering the temperature by

more than a degree or two produces a surprising change in the baby’s condition

and behavior. This response is so sensitive that we wonder how a

comfortable temperature is ever reached with clothing and blankets.

The discovery, which pleased us most, was

that crying and fussing could always be stopped by slightly lowering the

temperature. During the first three months, it is true, the baby would

also cry when wet or hungry, but in that case she would stop when changed or

fed. During the past six months she has not cried at all except for a

moment or tow when injured or sharply distressed-for example, when inoculated.

The “lung exercise” which so often is appealed to reassure the mother of a

baby who cries a good deal takes the much pleasanter form of shouts and gurgles.

How much of this sustained cheerfulness is

due to the temperature is hard to say, because the baby enjoys many other kinds

of comfort. She sleeps in curious postures, not half of which would be

possible under securely fastened blankets.

When awake, she exercises almost

constantly and often with surprising violence. Her leg, stomach, and back

muscles are especially active and have become strong and hard. It is

necessary to watch this performance for only a few minutes to realize how

severely restrained the average baby is, and how much energy must be diverted

into the only remaining channel crying.

A wider range and variety of behavior are

also encouraged by the freedom from clothing. For example, our baby

acquitted an amusing, almost apelike skill in the use of her feet. We have

devised a number of toys, which are occasionally suspended from the ceiling of

the compartment. She often plays with these with her feet alone and with

her hands and feet in close cooperation.

One toy is a ring suspended from a

modified music box. A note can be played by pulling the ring downward, and

a series of rapid jerks will produce Three Blind Mice. At seven months our

baby would grasp the ring in her toes, stretch out her leg and play the tune

with a rhythmic movement of her foot.

We are not especially interested in

developing skills of this sort, but they are valuable for the baby because they

arouse and hold her interest. Many babies seem to cry from sheer

boredom-their behavior is restrained and they have nothing else to do. In

our compartment, the waking hours are invariably active and happy ones.

Freedom from clothes and bedding is

especially important for the older baby who plays and falls asleep off and on

during the day. Unless the mother is constantly on the alert, it is hard

to cover the baby promptly when it falls asleep and to remove and arrange sheets

and blankets as soon as it is ready to play. All this is now unnecessary.

Remember that these advantages for the

baby do not mean additional labor or attention on the part of the mother.

On the contrary, there is an almost unbelievable saving in time and effort.

For one thing, there is no bed to be made or changed. The “mattress”

is a tightly stretched canvas, which is kept dry by warm air. A single

bottom sheet operates like a roller towel.1 It is stored on a

spool outside the compartment at one end and passes into a wire hamper at the

other. It is ten yards long and lasts a week. A clean section can be

locked into place in a few seconds. The time which is usually spent in

changing clothes is also saved. This is especially important in the early

months. When we take the baby up for feeding or play, she is wrapped in a

small blanket or a simple nightdress. Occasionally she is dressed up

“for fun” or for her play period. But that is all. The wrapping

blanket, roller sheet, and the usual diapers are the only laundry actually

required.

1The canvas and “endless”

sheet arrangement was soon replaced with a single layer of woven plastic, which

would be cleaned and instantly wiped dry.

Time and labor are also saved because the

air which passes through the compartment is thoroughly filtered. The

baby’s eyes, ears, and nostrils remain fresh and clean. A weekly bath is

enough, provided the face and diaper region are frequently washed. These

little attentions are easy because the compartment is at waist level.

It takes about one and one-half hours each

day to feed, change, and otherwise care for the baby. This includes

everything except washing diapers and preparing formula. We are not

interested in reducing the time any further. As a baby grows older, it

needs a certain amount of social stimulation. And after all, when

unnecessary chores have been eliminated, taking care of a baby is fun.

An unforeseen dividend has been the

contribution to the baby’s good health. Our pediatrician readily

approved the plan before the baby was born, and he has followed the results

enthusiastically from month to month. Here are some points on the health

score: When the baby was only ten days old, we could place her in the

preferred face-down position without danger of smothering, and she has slept

that way ever since, with the usual advantages. She has always enjoyed

deep and extended sleep, and her feeding and eliminative habits have been

extraordinarily regular. She has never had a stomach upset, and she has

never missed a daily bowel movement.

The compartment is relatively free of

spray and air-borne infection, as well as dust and allergic substances.

Although there have been colds in the family, it has been easy to avoid

contagion, and the baby has completely escaped. The neighborhood children

troop in to see her, but they see her through glass and keep their school-age

diseases to themselves. She has never had a diaper rash.

We have also enjoyed the advantages of a

fixed daily routine. Child specialists are still not agreed as to whether

the mother should watch the baby or the clock, but no one denies that a strict

schedule saves time, for the mother can plan her day in advance and find time

for relaxation or freedom for other activities. The trouble is that a

routine acceptable to the baby often conflicts with the schedule of the

household. Our compartment helps out here in two ways. Even in

crowded living quarters it can be kept free of unwanted lights and sounds.

The insulated walls muffle all ordinary noises, and a curtain can be drawn down

over the window. The result is that, in the space taken by a standard

crib, the baby has in effect a separate room. We are never concerned lest

the doorbell, telephone, piano, or children at play wake the baby, and we can

therefore let her set up any routine she likes.

But a more interesting possibility is that

her routine may be changed to suit our convenience. A good example of this

occurred when we dropped her schedule from four to three meals per day.

The baby began to wake up in the morning about an hour before we wanted to feed

her. This annoying habit, once established, may persist for months.

However, by slightly raising the temperature during the night we were able to

postpone her demand for breakfast. The explanation is simple. The

evening meal is used by the baby mainly to keep herself warm during the night.

How long it lasts will depend in part upon how fast heat is absorbed by the

surrounding air.

One advantage not to be overlooked is that

the soundproofing also protects the family from the baby! Our intentions

in this direction were misunderstood by some of our friends. We were never

put to the test, because there was no crying to contend with, but it was never

our policy to use the compartment in order to let the baby “cry it out.”

Every effort should be made to discover

just why a baby cries. But if the condition cannot be remedied, there is

no reason why the family, and perhaps the neighborhood as well, must suffer.

(Such a compartment, by the way, might persuade many a landlord to drop a “no

babies” rule, since other tenants can be completely protected.)

Before the baby was born, when we were

still building the apparatus, some of the friends and acquaintances who had

heard about what we proposed to do were rather shocked. Mechanical

dish-washers, garbage disposers, air cleaners, and other laborsaving devices

were all very fine, but a mechanical baby tender - that was carrying science too

far! However, all the specific objections, which were raised against the

plan, have faded way in the bright light of our results. A very brief

acquaintance with the scheme in operation is enough to resolve all doubts.

Some of the toughest skeptics have become our most enthusiastic supporters.

One of the commonest objections was that

we were gong to raise a "softie” who would be unprepared for the real

world. But instead of becoming hypersensitive, our baby has acquired a

surprisingly serene tolerance for annoyances. She is not bothered by the

clothes she wears at playtime, she is not frightened by loud or sudden noises,

she is not frustrated by toys out of reach, and she takes a lot of pummeling

from her older sister like a good sport. It is possible that she will have

to learn to sleep in a noisy room, but adjustments of that sort are always

necessary. A tolerance for any annoyance can be built up by administering

it in controlled dosages, rather than in the usual accidental way.

Certainly there is no reason to annoy the child throughout the whole of its

infancy, merely to prepare it for later childhood.

It is not, of course, the favorable

conditions to which people object, but the fact that in our compartment they are

“artificial.” All of them occur naturally in one favorable environment

or another, where the same objection should apply but is never raised. It

is quite in the spirit of the “world of the future” to make favorable

conditions available everywhere through simple mechanical means.

A few critics have objected that they

would not like to live in such a compartment themselves-they feel that it would

stifle them or give them claustrophobia. The baby obviously does not share

in this opinion. The compartment is well ventilated and much more spacious

than a Pullman berth, considering the size of the occupant. The baby

cannot get out, of course, but that is true of a crib as well. There is

less actual restraint in the compartment because the baby is freer to move

about. The plain fact is that she is perfectly happy. She has never

tried to get out nor resisted being put back in, and that seems to be the final

test.

Another early objection was that the baby

would be socially starved and robbed of the affection and mother love, which she

needs. This has simply not been true. The compartment does not

ostracize the baby. The large window is no more of a social barrier than

the bars of a crib. The baby follows what is going on in the room, smiles

at passers-by, plays “peek-a-boo” games, and obviously delights in company.

And she is handled, talked to, and played with whenever she is changed or fed,

and each afternoon during a play period, which is becoming longer as she grows

older.

The fact is that a baby will probably get

more love and affection when it is easily cared for, because the mother is

likely to feel overworked and resentful of the demands made upon her. She

will express her love in a practical way and give the baby genuinely

affectionate care.

It is common practice to advise the

troubled mother to be patient and tender and to enjoy her baby. And, of

course, that is what any baby needs. But is is the exceptional mother who

can fill this prescription upon demand, especially if there are other children

in the family and she has no help. We need to go one step further and teat

the mother with affection also. Simplified childcare will give mother love

a chance.

A similar complaint was that such an

apparatus would encourage neglect. But easier care is sure to be better

care. The mother will resist the temptation to put the baby back into a

damp bed if she can conjure up a dry one in five seconds. She may very

well spend less time with her baby, but babies do not suffer from being left

alone but only from the discomforts, which arise from being, left alone in the

ordinary crib.

How long do we intend to keep the baby in

the compartment? The baby will answer that in time, but almost certainly

until she is two years old, or perhaps three. After the first year of

course, she will spend a fair part of each day in a playpen or out of doors.

The compartment takes the place of a crib and will get about the same use.

Eventually it will serve as sleeping quarters only.

We cannot, of course, guarantee that every

baby raised in this way will thrive so successfully. But there is a

plausible connection between health and happiness and the surroundings we have

provided, and I am quite sure that our success is not an accident. The

experiment should, of course, be repeated again and again with different babies

and different parents. One case is enough, however, to disprove the flat

assertion that it can’t be done. At least we have shown that a moderate

and inexpensive mechanization of baby care will yield a tremendous saving in

time and trouble, without harm to the child and probably to its lasting

advantage.